The Value of a Velvet Rope: Effects of Hype and Exclusivity on Launch Strategies

By Gaby Goldberg & Jordan Odinsky

None of us are new to the idea of hype and exclusivity around drops and launches. Streetwear brands like Supreme and Yeezy are in the business of scarcity, where limited product releases supercharge the traditional supply-and-demand model, and where influencers, celebrities and fans alike create an “echo chamber of excitement.” Gaming and lifestyle brand 100 Thieves has become one of the hottest names in competitive gaming, in part due to its limited and highly sought-after drops of branded hoodies and t-shirts. Even dating apps like The League have built their brand around selectiveness and exclusivity, typically waiting to launch in new cities until hitting a large enough waitlist to maintain an approval rate of 20–30%.

It has some psychological ground, too: according to Rene Girard’s mimetic theory, we tend to want things simply because other people want them. Human desire is not an autonomous process but a collective one — this is how we decide what we care about. On top of this, life inside the velvet rope is, well, pretty good. There’s a real, psychological fulfillment of being “in” with the crowd and stoking envy among those around you. The idea of being “in” is an economy in itself: streetwear drops, exclusive social clubs, and now, as we’ve seen, viral consumer social products, which we’ll be focusing on for this piece.

There’s a new playbook for consumer and enterprise businesses alike on how to execute a successful launch. In this piece, we’ll analyze some of the most viral, successful launches in recent months and dissect the different strategies used. How were these launches successful in their own ways, and how did they each create their own version of a velvet rope?

Welcome to TestFlight

The playbook starts with TestFlight, an app that allows startups to soft-launch their own products before publicly hitting the App Store. Until recently, TestFlight was mainly employed as a place for a company’s inner circle to test an app, give feedback, and share bugs. Due to its “invite-only” nature, however, TestFlight has recently become a popular mechanism to stoke curiosity and build hype.

This wouldn’t be a piece on TestFlight launch strategies if we didn’t start with Clubhouse, an audio-social app capturing the zeitgeist of the current Silicon Valley tech bubble. Founded by Paul Davidson and Rohan Seth, Clubhouse is still in beta with less than 5,000 users. It’s worth around $100M in valuation. Where can you find Clubhouse on the Internet? Well, nowhere, really: there’s no landing page besides a link to the waitlist, and it’s not on the app store. Instead, users receive invitations to try the TestFlight beta privately on a case-by-case basis after joining an increasingly long waitlist. (Side note: For more information about Clubhouse, check out this comprehensive guide.)

Clubhouse didn’t employ this hush-hush launch strategy by accident. In fact, the founders launched another audio app, Talk Show, before Clubhouse (and there were plenty of other audio-social apps out there, too: Anchor, Bumpers, and TTYL, to name a few). The Clubhouse founders knew how to make this launch strategy successful, and they planned ahead. For years, they built up leverage by creating relationships with some of the most influential VCs and founders around the world. They also capitalized on word-of-mouth: buzz and momentum for Clubhouse came entirely from early fans and users. There wasn’t a paid ad in sight, and you didn’t see any Quibi-like user acquisition strategies floating around the tech Twitterverse (but more on Quibi later). Perhaps most surprisingly, Clubhouse didn’t even have a launch on Product Hunt. This secrecy was part of their success.

There are myriad products that experience explosive launch day growth, yet quickly cool off and become an afterthought as time goes on. Clubhouse stands out from this group, steadfastly remaining top-of-mind among the tech community since their private launch in mid-April. The genius of Clubhouse’s launch strategy lies in its social status machine: like the most successful cult brands, Clubhouse has set itself radically apart from the rest by consistently maintaining that it is only for the select few.

The Waitlist

Clubhouse garnered a massive waitlist of potential users hoping to pass through the velvet ropes of its Testflight doors. Their waitlist was a trickle-down invite model, becoming the modern-day version of a bouncer asking, “Which two friends do you want to bring in?” However, Clubhouse is only one example out of the many companies who have employed waitlists to build a similar sense of hype and exclusivity.

In early February, Basecamp co-founders Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson promised to bring a much-needed renovation to email as we know it with the launch of HEY, a simplified, potent email service that forces you to start from scratch. Within 24 hours of Fried’s Twitter announcement, HEY had already garnered around 13,000 people on its invite waitlist. Now, about six months later, the list is hovering somewhere around 100,000 signups.

HEY is a premium product, with no free tier besides a 14-day free trial. Instead, HEY users pay $99/year (with no option to pay monthly) for 100 GB of storage. For a two-character address (think ab@hey.com), the price jumps to $999/year. For a waitlist that long, it must be worth it, right? That’s not for us to decide — but we do know that the waitlist is effective in getting people excited.

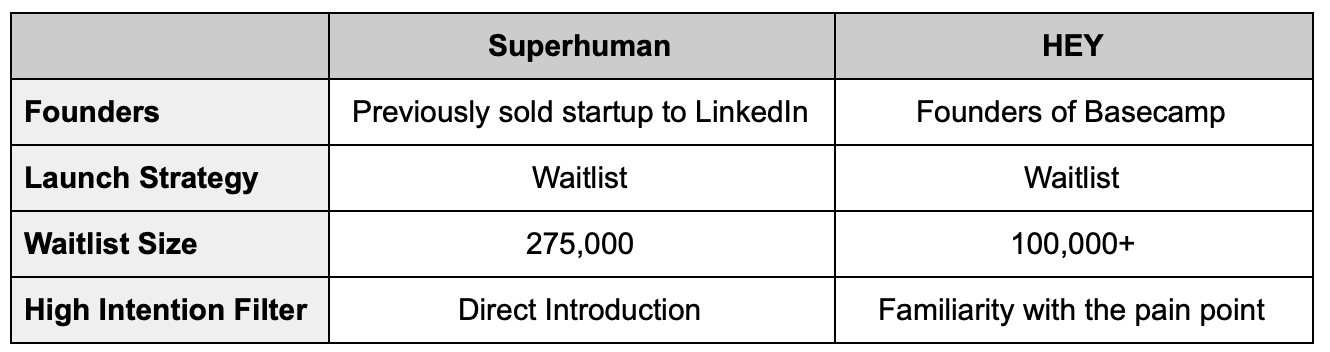

These waitlist case studies all tend to start the same way, with a Request early access or Grab an invite! call to action. They tend to end the same way, too: a Typeform asking for your name and email, and then… deafening silence. As customer acquisition costs rise, startups employ waitlists as a way to onboard small numbers of high-intention users, as opposed to large vanity numbers of low-intention users. This was clear in HEY, as well as in products like Superhuman and Pitch — when Superhuman launched, for example, the only way to get past the waitlist was to get an invite from someone already onboarded to the product.

It’s important for startups to employ some kind of filtering method to bucket potential users into low, medium, and high-intention users. These surveys and filters typically assess potential users’:

Role and seniority within an organization

Level of social status (by requesting social links, like a Twitter URL)

Current workflows and operating systems

Eagerness to use the product and familiarity with the pain point

Another case study of brands using waitlists to test consumer demand is the 2018 launch of Robinhood’s high-yield checking account. Robinhood set out to test both growth and consumer demand in one shot by developing a “social waitlist:” users were encouraged to share their unique signup link to move themselves further up the list. The result was a wave of word-of-mouth virality, with 90,000+ people joining the waitlist shortly after it went live. Spoiler alert: after the viral initial launch, it never got off the ground.

In short? Waitlists are a popular launch strategy, but they aren’t one-size-fits-all. Enterprise startups typically leverage waitlists while they stack their user base with impressive logos, thus increasing landing page signup conversion rate when they launch publicly. Consumer startups use waitlists to create network effects and ensure the product is sticky before opening up for business. As a general rule of thumb, waitlists should be used until startups see product-market fit markers (more on that here), and retired as the startup scales.

The Blue Check Phenomenon (Influencer)

We get an especially fresh take on exciting product launches from MSCHF, a Brooklyn-based ideas factory known for “capturing meme lightning in a bottle.”

“We build what we want. We don’t care,” says MSCHF head of commerce Daniel Greenberg. “If we can make people a fan of the brand and not the product, we can do whatever the f — k we want.” MSCHF sets aside no budget for advertisements and marketing, and conducts no user testing of its products. Instead, they partner with “blue check” influencers like Future, NBA athletes, and MrBeast (YouTuber with over 37 million subscribers) to add virality to their tongue-in-cheek products. MSCHF’s Drop 25, a $1,000 multi-brand collab shirt, sold out in less than an hour.

The same “blue check phenomenon” is seen with gaming and lifestyle brand 100 Thieves, which boasts Drake and Scooter Braun as two of its high-profile co-owners, and Cash App, Red Bull, Totinos, and Rocket Mortgage as commercial sponsors.

This trend is common in consumer & software products, too: companies like Clubhouse and Atoms have also employed influencer marketing as part of a larger launch strategy. When Clubhouse launched, they made sure to get positive press from a number of Twitter “blue check” influencers, like Oprah, Ashton Kutcher, Chris Rock, and Mark Cuban. And when Atoms was just getting started, they capitalized on positive public feedback from notable Twitter personalities, like Alexis Ohanian, Anthony Pompliano, and Ashley Mayer.

Building In Public

One of the most well-known leaders of the “building in public” phenomenon is Austen Allred, Founder & CEO of Lambda School. Allred largely built his company on Twitter, and those who followed him got to see him build Lambda in real time. Each tweet strategically related to Allred’s bold vision of reforming the higher education landscape; Allred encouraged his followers to engage and publicly brainstorm with him. Allred didn’t celebrate Lambda’s wins alone — he and his followers were all part of the same team. Like the underdog on a baseball team, Allred was the face of Lambda School and the underdog of the tech community. Each time he got on base, the crowd went wild.

More recently, the tech Twitter community watched a similar journey with Domm, Founder & CEO of Fast.co. He met his cofounder Allison Barr Allen through a cold DM, hired “probably half [his] team through Twitter,” and even made connections with VCs and angels through Twitter, leading Fast to a $20M Series A round in March. As Domm explained during an interview with The Takeoff, Twitter “can be amazing at driving community support and building teams, a community of investors, or a community of users and early adopters.”

What does this “building in public” phenomenon actually look like in action? For both Allred and Domm, it looked like vulnerability and authenticity. Their playbook for building in public looked something like this:

Share real quotes & screenshots of feedback from users

Propose interesting product ideas and ask the community for feedback

Articulate roadblocks the company is facing and how to overcome them

Give insight into largely unknown aspects of the company/product

Share “sneak peeks” and vague product updates for things to come

Post screenshots of internal Slack messages showcasing company culture

Tell emotional stories about your company to pull at followers’ heartstrings

Quote Tweet someone describing a problem and respond “We are fixing this at …”

Moneybags

For example, short-form TV app Quibi predicted 7.2 million subscribers by year-end. They launched on April 6th — now, they’re on pace for just 2 million, as millions deleted the service after their three-month free trial was over. Or think of Elliot, which invested huge sums of money into its marketing strategy, but ultimately had nothing to show for it.

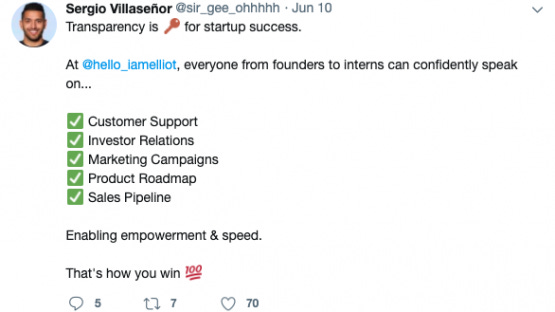

According to their pitch, Elliot was “going to be the anti-Shopify — an international e-commerce platform that focused on smaller businesses in an increasingly globalized world.” Elliot branded itself as hip and transparent, securing ad placements in newsletters like Lean Luxe and gaining traction on Twitter through inspirational (and easily shareable) threads.

Now-deleted screenshot (credit here) from Elliot CEO Sergio Villaseñor.

Elliot rode the direct-to-consumer wave of marketing first, product second, spending $800,000 on marketing, according to a court document from last January. Investor checks rolled in, and excitement began to build for their planned launch on June 18. When the day finally came, however, things began to unravel: the launch was abruptly pushed back to December 25th, and a few days later, the CEO announced that he was stepping down. Within 24 hours, Elliot was shut down completely in a “triage scenario” — with many employees learning of the demise through social media before any internal channels. Their fall from greatness was just as public as their rise up in the first place.

Wild Card

Lastly, of course, a piece centered around launch strategies and virality would no longer be complete without a reference to itiswhatitis (@itiseyemoutheye on Twitter), a mysterious meme that flooded the tech Twitter timeline in late June, leveraging the relentless hype of exclusive consumer apps. It reached top Product of the Day on Product Hunt, and its website accumulated over 20,000 email signups. Perhaps most importantly, itiswhatitis raised over $200,000 in donations to racial justice charities from people who “hoped to get special treatment within [the] fabled waitlist.” As written in this Product Hunt Daily Digest, itiswhatitis wasn’t a startup, or even a product. It was a statement, highlighting the influence of secrecy and exclusivity on the entire Silicon Valley tech community — and it will forever be an important case study of consumer virality in its rawest form.

As we’ve seen, there are myriad ways to launch a consumer product. At the end of the day, however, what’s the moral of the story? To begin, the launch isn’t everything: the hype cycle of exclusivity surrounding product launches only works when the shipping cycle is in sync. If the hype and shipping cycles aren’t working in parallel, and if the product itself isn’t there, then the launch strategy is useless. That said, if the product is ready to be launched, remember that viral consumer product launches don’t just happen by accident. Instead, it’s the combination of exclusivity + platform (in many of these cases, Twitter) that can skyrocket a concept from zero to hero with the right approach.

Footnote: In this conversation, it’s also important to note that most launch strategies don’t address the role of the unfair advantage, where a consumer product founder is someone of note and has their own exclusive access to people/resources not accessible to the general public. To highlight just some of these:

Superhuman was built by a second-time founder of a successful product bought by LinkedIn

Hey was built by Basecamp founders with a huge existing audience

Clubhouse was built by seasoned founders and tech minds, surrounded by an already-elite circle